Nobel Laureate’s discovery of the structure of DNA shaped our understanding of life.

James Dewey Watson, the American scientist who earned the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for co-discovering the double-helix structure of DNA, stands as one of the most influential figures in twentieth-century biology.

His work transformed our understanding of life at the molecular level and continues to shape research in genetics, medicine, and biotechnology. Later in his career, his role as a Fulbright Lecturer in Argentina underlined not only his scientific achievements but his importance as an ambassador for American research.

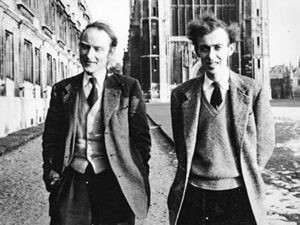

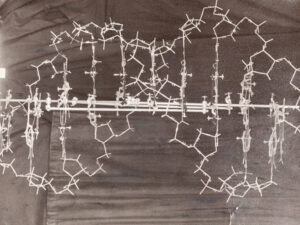

Born in Chicago in 1928, Watson demonstrated early intellectual promise, completing his undergraduate studies at the University of Chicago before earning a doctorate in zoology at Indiana University under bacterial-genetics pioneer Salvador Luria. His deep fascination with heredity led him to Cambridge University, where in 1953 he and Francis Crick proposed the now-iconic double-helix model of DNA, drawing on X-ray crystallography data from researchers Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins. This discovery revealed how genetic information is stored and replicated, a breakthrough widely viewed as ushering in the era of modern molecular biology.

Watson and his colleagues were key figures in the molecular biology revolution of the mid-20th century, which transformed understanding of biological processes at the molecular level and paved the way for new discoveries in gene therapy and gene modification, establishing the fields of genomics and bioinformatics. Watson later reflected that understanding DNA’s structure “opened the door to understanding the very basis of life.”

Watson’s influence extended well beyond his Nobel-winning research. For over a decade, he taught biology and conducted research at Harvard University, where he focused on the role of RNA in the transfer of genetic information and mentored promising young scientists. From 1968, he led the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, transforming it into a world-leading center for genetics and cancer biology. He championed interdisciplinary research, expanded training programs for young scientists, and built an environment that nurtured innovation.

In 1986, Watson was selected as a Fulbright Scholar to Argentina. He lectured on new developments in DNA research and gene manipulation at the Universidad National de Buenos Aires, and took part in an international science and technology fair that drew scientists from all over the region. For Argentine scientists, it was an opportunity to learn about cutting-edge developments in molecular biology, and his participation highlighted America’s scientific innovations and the Fulbright Program’s capacity to promote international engagement through strength.

From 1988 to 1992, Watson led the Human Genome Project at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). He championed the use of genomic research for early disease detection and pushed for more study into the societal impact and privacy risks of genetic research.

Despite a legacy complicated by his outspoken views, Watson’s achievements as a researcher, professor, and lab director exemplified the enduring power of scientific inquiry. His Nobel Prize-winning discovery remains one of the most significant scientific breakthroughs of the twentieth century.

Fulbright is commemorating the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence with stories of distinguished Fulbrighters who have showcased American excellence, innovation, and culture around the world. For 80 years, Fulbright has set the benchmark for global excellence and leadership in science, innovation, education, and culture.