Christopher Tin

Grammy-award Winning Composer and Musician

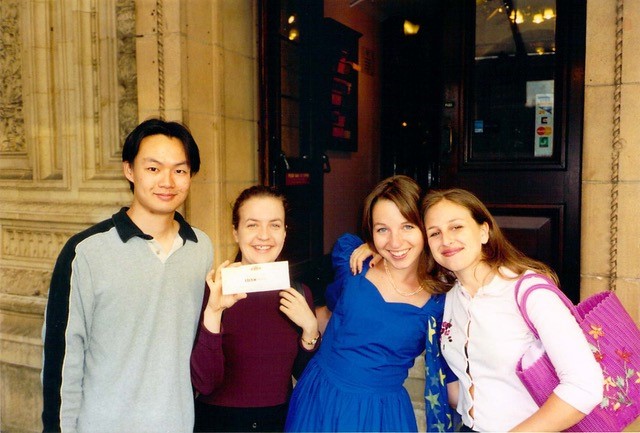

Fulbright U.S Student Study/Research Award to the United Kingdom

The work of Christopher Tin, a two-time Grammy-winning composer, ranges from lush symphonic pieces to world-music infused choral anthems and electro-acoustic film and video game scores. In 2024, Tin made an impressive debut in the opera world when he was commissioned to compose a new ending for the reimagined production of Giacomo Puccini’s venerable opera Turandot, which premiered at The Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

A Fulbright Award to study composition for the screen at the Royal College of Music in the United Kingdom served as an early step in his career in composition. “I’m immensely grateful that I got to spend a year abroad via the Fulbright,” he reflects, “not only because it gave me opportunities on two continents to further my professional career, but also because it gave me just a little extra insight into the lives of my parents, who took a similar journey a generation before me.”

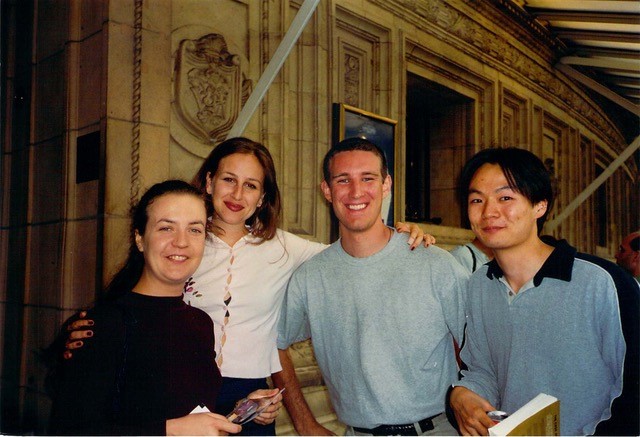

Tin grew up in northern California as the child of immigrants from Hong Kong. There, he was heavily influenced by jazz, musical theater, and the underground rave scene of San Francisco in the 1990s, along with his classical music training. While studying music at Stanford, he had an inspiring academic exchange semester at Oxford University.

Following graduation, Tin returned to the United Kingdom through the Fulbright Program. “The quality of the musical education I got at the Royal College of Music, particularly in their composition department, was second to none,” says Tin, and the impact on his career went beyond the academics. Fulbright “opened up many professional doors for me in the British music market,” and led to a job as a musical arranger on the staff of a British record label.

Tin continued to receive support from the U.S.-U.K. Fulbright Commission after he returned to the United States, recalling that they “generously wrote me a number of introductory letters to prominent composers in the film scoring world, which led to numerous internships and apprenticeships under some of the titans of the industry,” including an internship with the film composer Hans Zimmer.

While working on film scores in California, Tin attended his five-year Stanford reunion and had a chance encounter with his roommate from his Oxford exchange, Soren Johnson. Johnson was the lead designer on the video game Civilization IV, and their conversation resulted in Tin composing a new song for its opening titles. According to Tin, the song Baba Yetu channelled his disparate influences, including “African gospel, orchestral writing, and world percussion.” A Swahili setting of the Lord’s Prayer, the song became an instant classic and went on to make history as the first piece of video game music to win a Grammy Award.

Tin’s music reflects his lifelong interest in learning about other cultures. “As my own career in music flourished internationally, I’ve been fortunate enough to have visited many corners of the world to work with many musical artists—from South Africa to Bulgaria, Taiwan to Turkey,” he explains. “Working on a global stage has led me to write with the ethos of appealing as broadly as possible to people from as many backgrounds as possible, often by speaking to universal themes shared by all people across borders, cultures, and religions.”

He received his second Grammy for the classical crossover album Calling All Dawns, and his following release, The Drop That Contained the Sea, premiered to a sold-out audience at Carnegie Hall’s Stern Auditorium. It was his first Grammy-winning video game score, however, that brought him to the attention of the Washington National Opera’s (WNO) Artistic Director Francesca Zambello, who heard his music while her son was playing Civilization IV.

Puccini died while still writing Turandot, and the opera was later completed based on the notes the composer left behind—but questions remain about the author’s original intent for his characters. On the centennial of the Italian composer’s death in 1924, Zambello wanted to use the opportunity of the work entering the public domain to present his final unfinished opera with a new ending. Zambello explained that the story “reinforces some problematic stereotypes not just about China, but also about women.” She sought an ending that could address the way the princess’s story was resolved and challenge the opera’s orientalist themes. Tin was one of two Asian-American artists that Zambello approached, along with playwright and screenwriter Susan Soon He Stanton, to write 18 minutes’ worth of new material that would finish the opera and update it for a modern audience.

The new production was one of the largest that WNO has ever staged. Its opening was accompanied by community events, with Tin and Stanton discussing the challenges of reimagining portions of a beloved and widely performed opera. Events included an exhibit at the Chinese American Museum and a panel discussion called “A Turandot for Today,” inviting people from diverse backgrounds to use opera as a prism to examine and candidly discuss contemporary issues. The Kennedy Center also hosted a “Christopher Tin Sing-In,” inviting members of the public to learn and sing along to the new material accompanied by the Washington Metropolitan Gamer Symphony Orchestra.

After two decades of writing classical music and scoring films and video games, this opportunity has given Tin a fresh perspective. “Being part of WNO’s new production of Turandot has honestly been one of the highlights of my career,” he reflects. “Being part of such a major production, with my music as one of the central focal points, has been exhilarating. It’s also opening up a lot of doors for me in the opera world, and I’m looking forward to composing my own full opera at some point.”